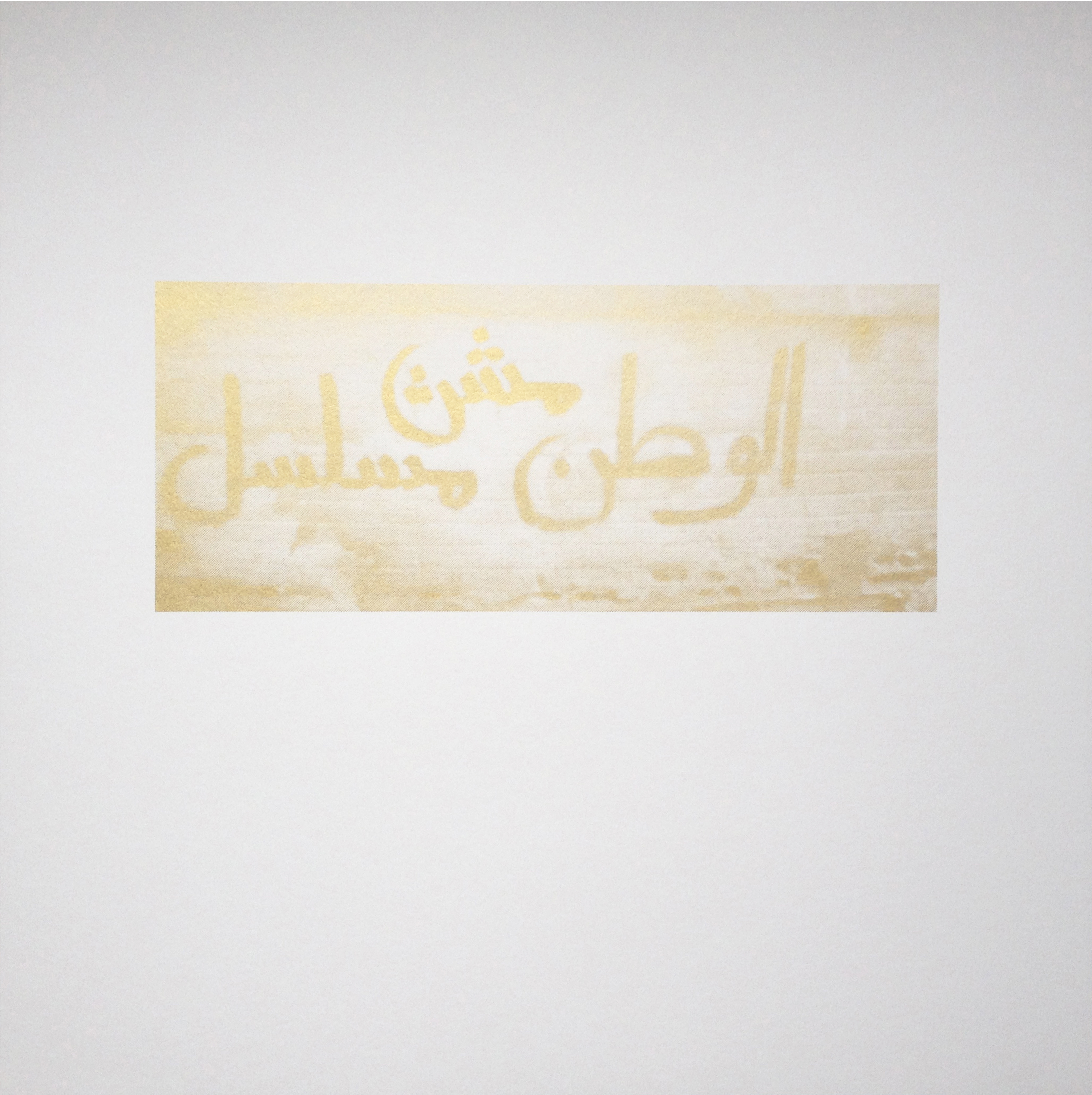

This Show Does Not Represent the View of the Artist (Homeland Is Not a Series), 2016. 70 x 70cm, gold pigment on paper, silkscreen.

The set of prints titled “This Show Does Not Represent the View of the Artist” is a small series of silkscreens I made to commemorate the Homeland graffiti hack, which I learned of around five months after it occurred. I was struck by its strong gesture of rebellion and its brilliant simplicity. For the past twenty years, my work has been based on uncovering ideological subtexts within popular culture; it’s the basic material of inquiry for my artistic practice, which expresses itself in diverse media ranging from drawing and print to film and video. The Homeland hack infiltrated and exposed a narrative of bigotry and racism in the entertainment industry, and for me, particularly in view of the dangerous political climate in the United States, this was a source of personal inspiration—and cause for celebration.

The homage that This Show Does Not Represent the View of the Artist pays to this act of rebellious genius was and remains exactly that: an homage, a tribute, and a celebration.

Operating with a subversive, Trojan Horse-like artistic strategy, the group posed as Street Artists in order to get hired to supply Arabic graffiti—any old Arabic graffiti—to decorate the background of a TV set. This was the subterfuge necessary to conceal their intentions, and it worked. The fact that no one on the production set understood a word of Arabic already speaks volumes. The group essentially entered into a fictional narrative posed as a fictional entity to underscore the racist hatred underlying the distrust of the Muslim population that took hold after the September 11 attacks of 2001. By and large, the press coverage on the incident was unaware that this was not an act carried out by “mere” graffiti artists, but an actual artistic intervention; consequently, I only learned of this fact after I presented the work at the Berlin Art Fair. To my mind, the fact that I, a fellow artist, would unwittingly—but instinctively—pick up on this and reimport it into my own work seems like a logical extension of this political and artistic act, and entirely in keeping with the disguised nature of the intervention.

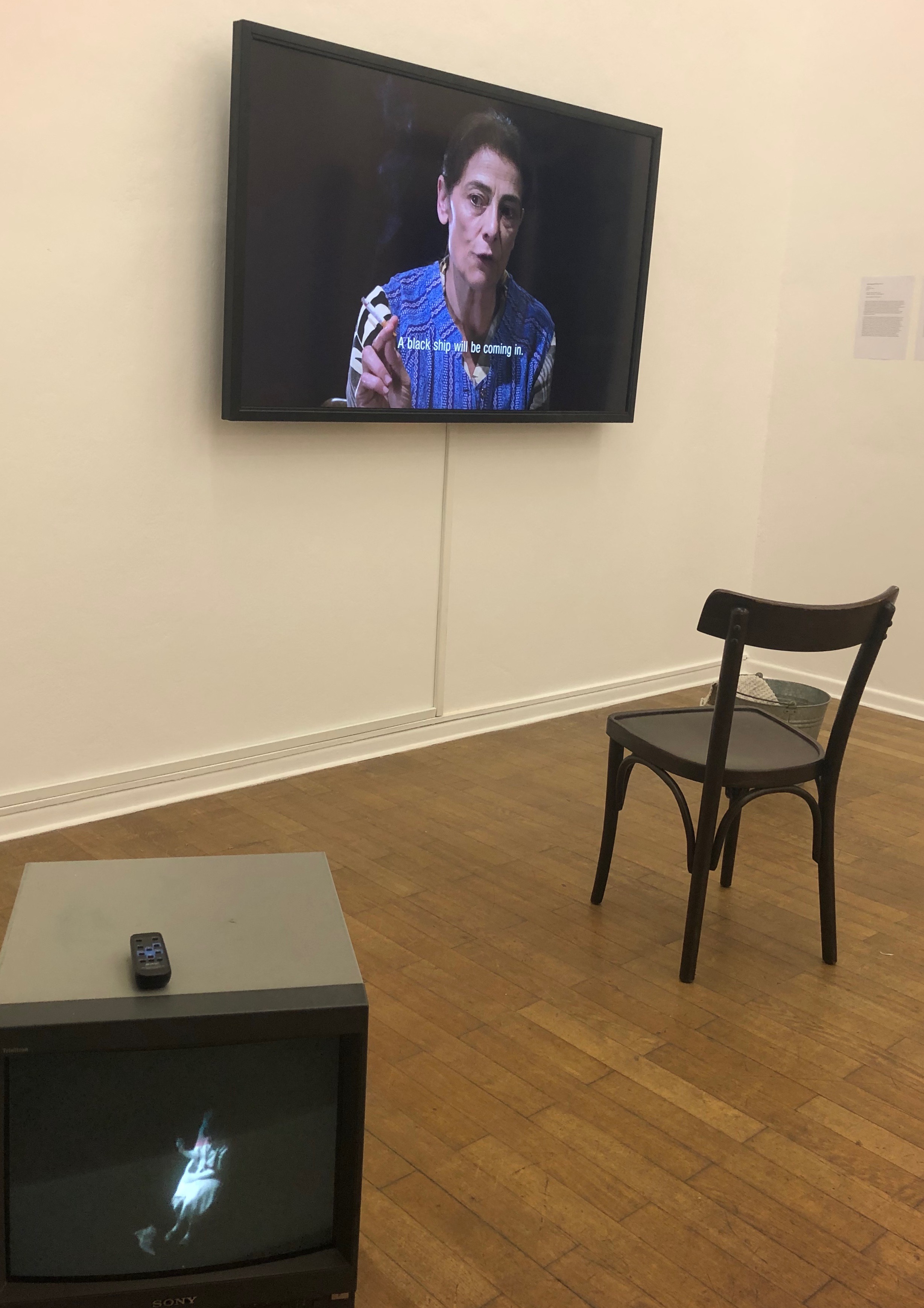

Many accusations have been leveled against the work: that it’s a white male artist stealing the narrative from the marginalized, that it’s tone deaf, etc. My only answer to these claims is that the body of my work lends a substantial context to this series that makes its intentions clear. I’ve deconstructed the iconography of Hollywood films to expose the true ideologies lurking behind the surface glamour and the American obsession with celebrity; I’ve worked several times with Palestinian actress Hiam Abbass on films that address issues of identity, home, and economic exploitation in an increasingly unstable and volatile world. My work draws on both popular culture and art history, classical opera, Brechtian theater, and day-to-day news, and its aim is political and social criticism.

We live in an age of sampling and appropriation, and an important part of my practice is firmly situated within this formal strategy. I was therefore operating in a vein similar to what I have been doing for many years: appropriating images from films and media and recontextualizing them to expose and rearticulate the true narrative at hand. Convinced that the Homeland hack was external to the art world, I chose a selection of the graffiti and printed them in gold as a gesture of inspired celebration to honor this story. The use of gold creates a reflective surface, with the image appearing and disappearing according to the position of the viewer. This instability underlines the volatility of media images, which quickly vanish from our memory as important stories are forgotten and replaced by newer ones. The unprofessional photos that have been posted on the Internet do not do the work justice.

I was not “stealing” anybody’s narrative. Homeland is a product of the US entertainment industry, and my homage to a hack at its expense also becomes my narrative, as I have been exploring precisely these issues of cultural identity, belonging, displacement, misrepresentation, and scapegoating for over twenty years.

I grew up between many cultures and languages, with issues of geographical and cultural displacement, non-acceptance, Anti-Semitism, and non-belonging informing both my personal biography and my professional work. Nonetheless: identity politics do not interest me; often enough I’ve seen them obstruct a wider, far more challenging dialogue. As artists, surely we’re smarter and braver than policing art production and adopting the guise of moralistic obedience. I have never limited my field of interest or sense of empathy to any one particular culture, skin color, or gender. If this makes me a controversial artist, then I fully embrace it.